By Jay Moore

Adapted from a portion of “Abilene History In Plain Sight” published by ACU Press.

An average Tuesday morning in downtown Abilene was delightfully enlivened in August of 1917 as Company I of the Texas National Guard came unexpectedly marching along Pine Street. People stopped to watch and to offer their encouragement, clapping, whistling and hooting hoorays as the local lads of Company I proudly strutted in precision, stepping in time and belting out their theme song “To Hell With the Kaiser.”

We will give the Kaiser hell in his home across the sea;

We will shoot him squarely in his own aristocracy!

As we go marching on.

With their mismatched uniforms drenched in sweat, the youthful contingent turned and smartly marched west along South First Street, back toward their two-week old Fair Park bivouac dubbed Camp Parramore. (Named in memory of local cattleman, Civil War officer and ardent Abilene booster James Parramore who had passed away only weeks earlier.)

For just a few sweltering weeks in the summer of 1917, Fair Park (now Oscar Rose Park) was a beehive of military activity as the United States prepared to enter World War I. Governor James Ferguson had called on Texans to volunteer for service as the country moved to enter the three year old conflict. In Abilene, over 150 young men from Taylor, Jones and Callahan counties stepped forward to create Company I of the 7th Texas Infantry.

Little encouragement was needed to urge the patriotic boys to join up. With the Abilene Gas and Electric Company offering a spare room and desk to serve as the enlistment office, Abilene merchant and recently commissioned Lieutenant Alan McDavid prepared to handle the enlistees. On Monday June 18, 1917, when McDavid opened the door to begin the process, he found four eager young men already waiting. First to enlist was Curtis Kean – better known as “Cooter” – followed by Joe Robinson of Buffalo Gap, Edward Fillmon from Ovalo and Abilenian Henry Waldrop, son of a former county commissioner. Before the week was over, forty more had taken the oath, including Ben Fuller, the son of the district clerk who had enthusiastically signed up for the volunteer regiment but needed his father to accompany him to Lt. McDavid’s office and sign a minor’s release since young Ben was a few months shy of enlistment age. Many were encouraged to sign up with the assurance that they would be serving alongside their fellow locals and under the command of an Abilene officer.

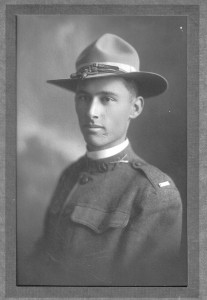

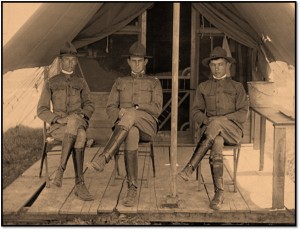

One month into enlistment, the outfit of 150 was officially mustered into service with Company I and placed under the command of native Abilenian Robert M. Wagstaff, son of well-known local attorney John Wagstaff who also served as a member of the three-person county draft board. Young Captain Wagstaff was enrolled in the University of Texas but was already on temporary leave to patrol along the Mexican border near Brownsville as that country’s revolution heated up. Summoned home to serve, Wagstaff was very pleased when he found that his first cousin Ted Sayles had been commissioned Second Lieutenant due to his prior military service and his Boy Scout experience. Along with Lieutenant McDavid, Wagstaff and Sayles formed the officer corps of the brand new company. The three set up their headquarters at Fair Park in the women’s restroom.

For four weeks the West Texas lads would camp and train in the park before moving out to Camp Bowie in Fort Worth. Reveille was sounded at 6:10 each morning rousing all for a day that included three hours of marching and learning military basics. In their free time, the boys spruced up the park for the approaching West Texas Fair. Abilene evidenced strong support for her local boys as they began training under a scorching summer sun. Although lacking proper uniforms and military equipment – drilling with broomsticks for guns – there was more than enough local bolstering to buoy their spirits. Mrs. K.K. Legett treated the camp to a watermelon feast, followed the next day by a noontime barbecue hosted by Colonel Clabe Merchant and his son Mack and served by Abilene business leaders. Mrs. Dallas Scarborough organized a carnival to raise mess funds for the troops to carry with them once they were sent abroad. Cots were donated so the boys would not have to sleep on the floor of the automobile building at the park.

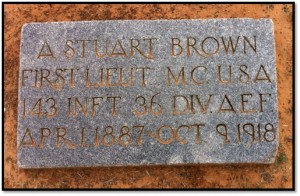

As Captain Wagstaff worked to prepare the group for an impending encounter with far away German forces, local physician and army Lieutenant Stuart Brown conducted physicals, determining that only 141 of the group were fit for service. The non-qualifiers were deemed to be underweight.

On September 1, the city hosted a huge sendoff before the men boarded a special troop train surrounded by relatives, friends and sweethearts as the men moved east to Camp Bowie and one step closer to the Western Front. At Camp Bowie they would finally receive uniforms and be consolidated with the 1st Oklahoma Regiment to form the 142nd Infantry, one of the four regiments comprising the Thirty-Sixth Division. While in Fort Worth the group marched in the largest military parade ever held in Texas as more than 200,000 watched the four-hour parade pass along Main Street. Training would continue for ten more months but was tragically marred by an accident in May of 1918 when a mortar exploded during a training exercise killing eleven, including four Abilene boys. Jess Ellis, Alfred Woodle and Morgan Sanders were killed, as was twenty-nine year old Lieutenant Alan McDavid.

Following a train trip to New York in early July of 1918, the Fair Park boys boarded a former Dutch passenger liner, now commissioned as a U.S. transport ship, the USS Rijndam and sailed down the Hudson River past the Statue of Liberty and steamed their way to the European fight. It was an uneventful 12-day crossing although, as they neared the coast of France, a German sub caused a bit of excitement. The worst most had to deal with was the seasickness.

The Abilene boys arrived in France at a critical moment in the war due to an earlier spring offensive by the German army in which they hoped to end the war before U.S. troops could join the fight. By summer it was clear that the series of German offensives failed to achieve their strategic objectives, opening the way for the insertion of American troops. The 36th was imbedded with the 4th French Army and, following a week of rest, boarded trains to take them within one hundred miles of the front. At a base known as Training Area 13, the soldiers were conducted on how to attack machine gun posts along with live grenade training and bayonet drills. Captain Wagstaff had been summoned to Paris as his troops continued to train in his absence.

On Sept. 26, the same day that American forces launched the decisive Meuse-Argonne offensive, the 36th Division began to march toward the front line trenches, entering the forward battle area on Oct. 4, 1918. With instructions to now leave their blankets behind, the 142nd lead the brigade forward to the front line trenches on Oct. 7. Lieutenant Ted Sayles was in charge of the 37mm cannons and had struggled to move troops and artillery northward. Sayles could see flashes of light and a steady glow on the horizon from fires started by exploding artillery shells. Moving ever closer to the front, he saw flares shooting into the sky, and in their dim light saw what he later described as a “skeletal forest of shattered tree trunks, winding rows of chalky earth from deep trenches, piles of rocks, and ghosts of walls.” Crossing over the defunct Hindenburg Line, the boys took up positions near St. Etienne

The Fair Park boys went into line with the American 141st Infantry on their right and French forces to their left, facing a battle-scarred terrain which had been fiercely fought over for the previous four years. The landscape was a flat, open ground strewn with German wire and trenches and a ravine just beyond at the bottom of a wooded slope controlled by the enemy. Far from Abilene and West Texas, they were now a mere one hundred yards from German fortifications.

The night of Oct. 7 was spent settling into their unfamiliar, other-worldly surroundings and staying busy in order to suppress the anxiety and anticipation. A seeping dread was present with the knowledge that the order to leave the relative safety of the trenches was imminent, knowing the only direction for them was into the terrible tumult of World War I. That awful moment came much sooner than expected. At 5:30 the next morning – Oct. 8 – the Abilene boys checked their weapons, collected their courage, suppressed an overwhelming panic and – far, far from home – gallantly went over the top side-by-side, moving east and sending artillery rocketing across no-man’s land in hopes of clearing a safe corridor. Advancing through blinding smoke, deafening noise and sustained machine gun fire, the boys ran through the hazy pre-dawn light, strangely lit from the flashes of constant shelling – a tableau accompanied by the eerily high pitch of whizzing bullets, yelling men and the stunning screams of soldiers in agonizing pain, passing others posed silently in death.

Despite the mayhem and tumult of war, most of those who stepped forward to form Company I would live to see another sunrise. But not all. Among those losing their lives in the flashing fire outside of the French village of St. Etienne was young Ben Fuller – dying just 32 days before the end of the war. The same day, Abilene doctor Lieutenant Stuart Brown would also die in the mud of France. It would take four years before their bodies arrived back home in Abilene. Stuart Brown’s funeral was held at his church, the Episcopal Church of Heavenly Rest where today a stained glass window given in his memory allows western light into the chapel. Fuller and Brown are both buried in the City Cemetery along Cottonwood Street. Hundreds gathered as Private Ben Fuller’s body was carried to his grave on a Sunday afternoon by his fellow soldiers; his sacrifice was honored with three rifle volleys and the somber notes of “Taps.”

Robert Wagstaff and his cousin Ted Sayles survived the war and came back to Abilene. Ted would later make Arizona his home while making a name for himself as an archaeologist. Captain Robert Wagstaff would practice law while spending the rest of his life in Abilene. He died in 1973

The boys of Company I mustered out of service in June of 1919. The following month, on July 4, Abilene organizers met at Fair Park to create the Taylor County American Legion, choosing to honor the boys of Company I. The post was named after the camp where the Abilene boys trained – Parramore Post. Nearly a century later, the post remains active and is located on East South Eleventh Street. A historical marker located in Rose Park notes the contributions of the local boys who were part of Company I.

Nov. 11, 1918 brought an end of the hostilities of World War I and will be forever remembered by our observance of Veteran’s Day.

Is there a list of names posted who served? Looking for Cecil Harris