In 1963, integration of Abilene public schools began, and in 2016, a new marker honors that historic event.

By Loretta Fulton

Photography by Doug Hodel

The two older white women and a younger black woman walked toward each other, smiling and talking as if their history-making day 53 years ago had happened just yesterday.

On Feb. 22, the three women were reunited at a ceremony dedicating a Texas Historical Commission marker at Dyess Elementary School, where integration took its first step in Abilene on Jan. 21, 1963.

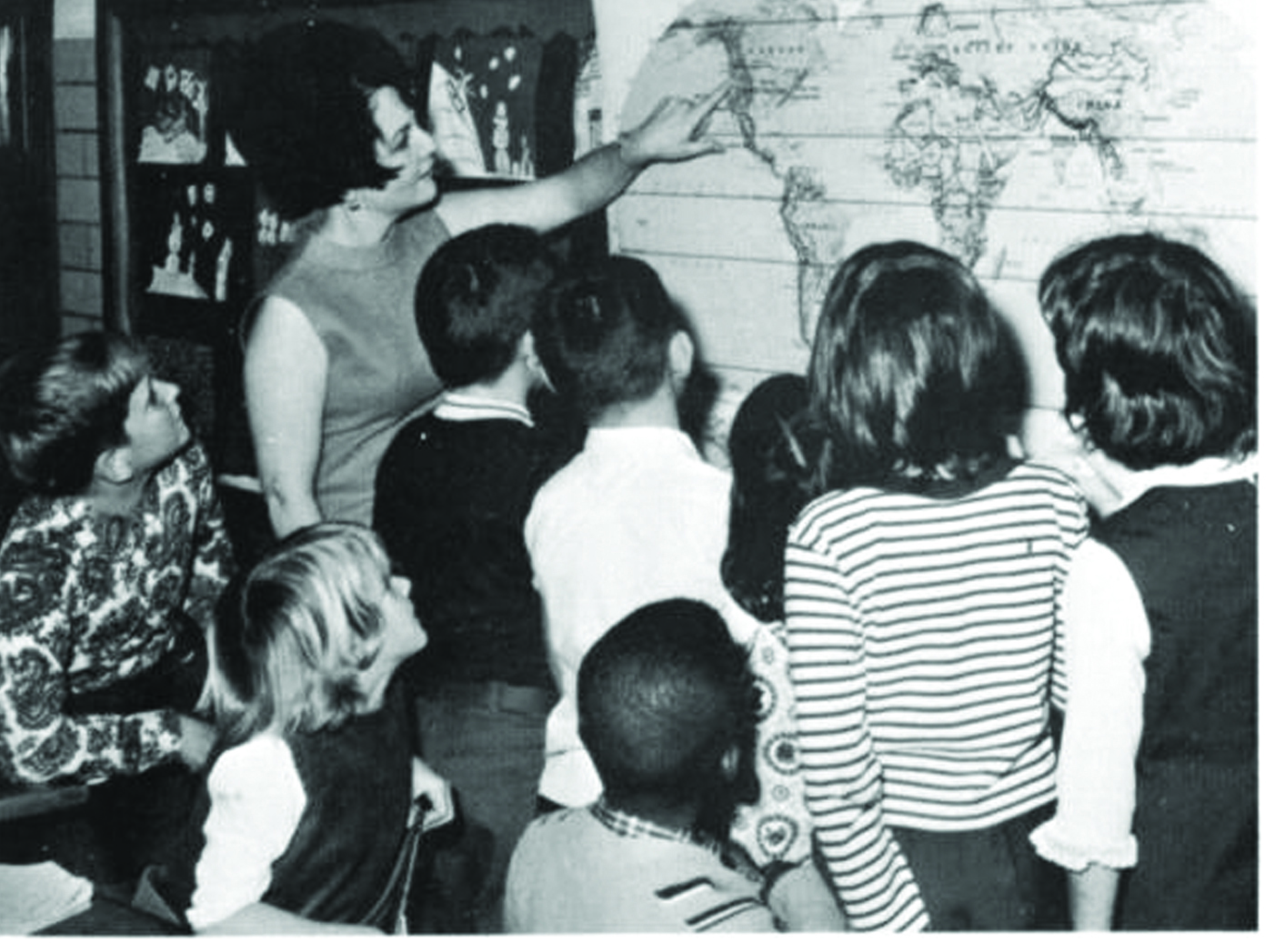

Maxine Williams and Nelva Turner were teachers that day in 1963. Betty Lattimore, now Jones, was in first grade. She had started school in the fall of 1962 at Woodson Elementary School, reserved for black children and located across town from Dyess Elementary.

But that cross-town bus trip ended on Jan. 21, 1963, and the move toward total integration of the Abilene public schools began. Each year after 1963, higher grades would be integrated so that by 1968, all of the Woodson schools would be closed.

Feb. 22 was devoted to celebrating the ending of a wrong and the people who brought about that change. It also was a day devoted to celebrating the lives of the people involved that January morning who made the transition to integration as smooth as possible. The conversations sounded like any other reunion after 53 years.

“Can you imagine Stevie being a grandfather?” Jones asked the two older women.

“Stevie” is Steven Lattimore, Jones’ younger brother who attended Dyess Elementary School after it was fully integrated. He now is an aide at Madison Middle School.

The three women chatted and hugged. The two former teachers talked about being on the right side of history.

“It feels good,” Turner said.

They recalled that despite the enormity of the move and the civil rights unrest going on nationwide, the first day of integration in Abilene passed with little notice.

“It couldn’t have been any smoother,” Williams said.

Dyess Elementary School was the logical choice for the first school to be integrated in Abilene. The airbase itself was integrated, with children of all races playing together on the grounds or in each other’s homes. When families transferred to Dyess, they were accustomed to integrated schools and were shocked at the segregation in Abilene. Betty Jones’ family, the Lattimores, came to Dyess from Okinawa, where segregation was unheard of.

For Jones, always laughing, with no trace of bitterness about the past, that historic day in 1963 was unremarkable. The only difference was that she didn’t have to get on a school bus, and she got to go to school with the white kids she was used to playing with in the playground of the housing unit where her family lived on Dyess Air Force Base.

“It was a day that happened at 8 in the morning and ended at 2:30,” she said. “I got to walk to school with my friends.”

What Jones didn’t realize when she was a first-grader was that her mother was one of the people behind the move to integrate Dyess Elementary School. Her mother, the late Alberta Lattimore, and four other mothers of black children wrote a letter to A.E. Wells, who was superintendent of the Abilene schools at the time.

A black father and Harvard College graduate Capt. John Rice also wrote a letter “after a great deal of soul searching and contemplation” questioning why his children could not attend Dyess Elementary School, an easy walk from their home.

The letters, and other pressures, brought about a monumental change, one that occurred seamlessly but went unrecognized in an official way until Dyess airman Tremayne Hubbard, president of the African-American Heritage Committee at Dyess AFB, learned of it.

“I was a little bit in shock,” said Hubbard, who has been stationed at Dyess for seven years.

A history buff, Hubbard got to work, joining forces with Andrew Penns, a local black pastor and member of the Taylor County Historical Commission, as well as Anita Lane-McBride, chair of the commission. In record time, Hubbard researched the integration of Dyess Elementary School, sought direction from the local historical commission, filed an application with the Texas Historical Commission, and got the marker approved.

A mock-up was in place for the dedication while the official marker awaits casting. When it arrives, it will be installed in a flower bed in front of the school.

Much of the research that Hubbard conducted came from school board minutes of 1962 and 1963 and from a doctoral dissertation written in 1994 by Steven Kent Gallaway, an Abilenian who was earning a doctor of education administration degree from Texas Tech University.

“I’m just tickled to death that somebody read it,” Gallaway said, noting that usually only the review panel reads doctoral dissertations.

Betty Jones has come full circle since walking to Dyess Elementary School on Jan. 21, 1963. She joined the Army in 1988. She served in Germany and at Fort Sill, Okla., before her discharge in 1996. She moved back to Abilene in 2003 and married Abilenian James Jones. Today, the Jones family lives within shouting distance of Dyess Elementary School.

Her family ties to Dyess AFB run deep. Her dad was stationed at Dyess and retired here in 1974. Even though both parents were from Mississippi, Jones said they never thought of leaving Abilene once they separated from the service.

“Back then, that was the norm,” Jones said. “There were so many jobs to go into.”

Her dad, Herbert Lattimore, worked in bank security and as a guard at Abilene Lumber, known to many Abilenians as “Big Mo.”

There were six children in the family when Jones was growing up. Her dad was gone a lot due to being in the Air Force. Jones had no idea her mother had helped pen the historic letter that spawned the integration move in Abilene.

It wasn’t until about 10 years ago, when an older sister mentioned how upset their parents had been about the children having to be bused across town, that Jones became aware of the letter. She was surprised, remembering her mother’s nature.

“I didn’t think my mother had that in her,” Jones said. “I was real proud of her.”

Six years after the historic January day in 1963, Ocie Lacy Jr. walked into Dyess Elementary School as a teacher, most likely the school’s first black teacher. He was a product of the Woodson school system, graduating as valedictorian of his class in 1959.

He earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Texas at El Paso and later taught there. He remembers the one year he taught at Dyess Elementary and how proud he was. He recalled taking his 175-voice school choir to sing Christmas carols in front of the old Thornton’s Department Store, which was famous for its elaborate Christmas displays.

He was proud not only of his school kids, but also of their parents. Only 10 of the children in the choir were black, but that didn’t matter to the parents, white or black.

“It just felt so great having all those parents there,” Lacy said in a telephone interview from his home in New Jersey, where he has lived since 1975.

Lacy said he didn’t know what to expect when he arrived at Dyess Elementary School as a teacher in 1969, but he soon earned the respect of the children and their parents. He liked perfection and discipline, which he found in abundance at Dyess Elementary School.

Even though Lacy couldn’t make it to Abilene for the marker dedication in February, just knowing a marker exists was enough.

“It makes me have a big chest,” he said.

I went to Dyess elementary and played with the Lattimore’s when we were young children. Jo-Jo, Stevie, Betty… lived across the street from us in early 1960’s when my father was stationed at Dyess. I never knew about the segregation at that time.